OVERVIEW

The Latest Book by U.R. Bowie

First published in 1842, Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls still ranks as one of the most prominent comic novels in the history of world literature. U.R. Bowie, Ph.D., who taught Russian literature for thirty years at Miami University, delves into the book’s multivarious themes and stylistic quirks, including, e.g., the grotesque in Gogol, the socio-political thematics, the leitmotif of boots, the metaphysics of Dead Souls, irony and satire, misogyny, the theme of the creative imagination, names and naming, the leitmotif of food, megalomania, the laughter of Dead Souls, verisimilitude, expanded metaphors and digressions, liars and lying, the music of Gogol’s prose, the leitmotif of the road, stylistic skazifications, authorial prolepsis, narrators omniscient and otherwise, the leitmotif of dumbfounded, and more. In an appendix six different translations of the novel into English are compared and evaluated.

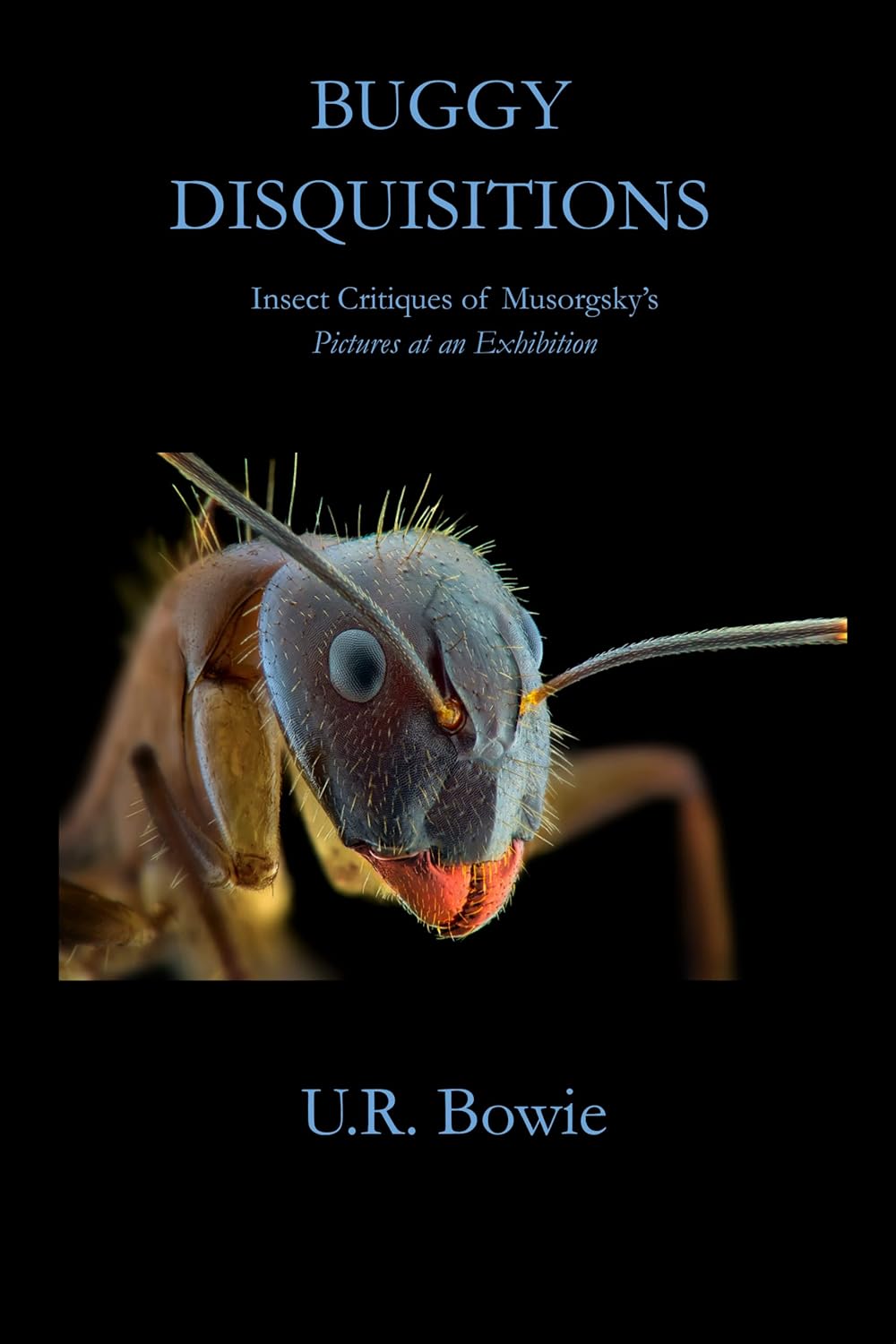

Under the editorship of a dragonfly, a consortium of the six-legged, plus, for the flavor, a single eight-legged, come together to write a book of musical criticism on one great work from the treasury of classical music: Modest Musorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

The six-legged (insects): the rainbow scarab beetle, the Florida lovebug, the spittlebug, the army ant, the Smoky Mountain lightning bug, the black and yellow mud dauber, the Anopheles mosquito, the phoretic beetle mite, the American cockroach. The eight-legged: the ballooning spider.

Utilizing their special expertise on such things as the sounds of pullulation, the music of a silent pond at dusk and the orchestration of stridulations, these critics present their special insights into Musorgsky’s music, while complaining bitterly about the desecration of the environment they live in and proselytizing, as well, for the buggy way of life on God’s Green Earth.

A potpourri of thoughts, ruminations on life as it is lived in the coronavirus year of 2020. A kind of diary of the Covid Year, complete with cogitations on any number of things, by the author and by great thinkers throughout history. Among other things, the book includes commentary on the American political morass of our time, quoted poetry, nonsense verse, philosophical musings, and analysis of literary works.

Looking Good takes a long hard, but frequently humorous, look at life in America in the nineties. Its major themes include racism, sexual violence, mothers and sons. It emphasizes the ways people look at, or refuse to look at, themselves, others, and life.

The action of the novel revolves around a sensational episode that actually occurred: the gang rape (or non-rape) of a white woman by a large number of black professional football players from Cincinnati. The viewpoint of working class white America toward blacks, Native Americans, and other minorities is broadly treated. In a book about racism the very narrative is suffused with racist views; there is, however, no overriding didactic message. Looking Good tries to show how people are: bad and good simultaneously. Neither the white racists nor the black rapists in the story are portrayed as monsters.

Each chapter is composed of a series of short sub-chapters. Some of these describe childhood, or future, events in the lives of the football players and the woman they raped (or didn’t). Ancillary stories, meanwhile, develop the novel’s main themes. An old homosexual couple journeys to Florida, to swim with the manatees. Work progresses toward completion of the monument to Chief Crazy Horse in South Dakota. Reading his morning paper in Indianapolis, a working class white man ruminates, angrily, on his country’s problems. Periodically, the author of Looking Good, O. Beauvais, takes a break from composing his novel to bemoan the psychic hazards of describing violence in fiction.

Looking Good takes a look at sex cannibal Jeffrey Dahmer, at manatee homosexual behavior, at radio talk show racism, at the yellow-bellied lizard (scheltopusik), at Lakota Sioux shamanic traditions, at middle class political correctness, at the ways people are kind, or horribly cruel, to one another, at the amazing fact that anything can happen in life. Anything. Even happiness.

Book Description: Cogitations on the White Whale: A Palaver Novel in One Sentence

Poised on the edge of the Octogenarian Age, Hezekiah Hopewell, palaverer extraordinaire, reads Moby-Dick and talks, talks, and talks. In fact, he talks and sings his way without stopping through a short novel of 50,000 words. Inspired by Bohumil Hrabal’s novel in one sentence, Dancing Lessons for the Advanced in Age, U.R. Bowie’s Cogitations cogitates on a wide variety of issues and themes:

the prevalence of self-declared Messiahs in human history, the outrageous cost of dental care in the U.S., how to train a pet lizard to bark, beg and fetch, ways of committing suicide, including holding your breath, the smell of irradiated horse chestnut leaves in Kiev, autumn of 1986, modern-day hate-drenched America, the return of the Saviour for a look around at the world, two thousand years after He was last here, the way global warming threatens the frozen sighs of seals, polar bears and Eskimos in Alaska, how to hold your mouth and face when having your picture made for a Russian passport,

the way beautiful old words are threatened with extinction in our wordless, incoherent age, the Christian ascetics known as Stylites, the ephemeral three-day existence of the Florida love bug, how to make a good living selling ambergris gathered from the guts of sperm whales, what to do with old age when it stares you in the face, why Jonah in the bible was vomited out of a whale onto dry land, why the Pope wears a little white cappie, and why that annoys the human race, why there are no whys on earth (because there are no becauses), and much, much, much more.

What has Hezekiah Hopewell done with his long life? Well, he has been married to four different women. Lucky for him, since he has never had a job and his wives have supported him. He has not really done much of anything but read books. Now, fast approaching deep old age, Hezekiah drives around with his nephew Hiram—“a man steeped in self-rectitude, ineptitude, rednecktitude”—in a rusted old jeep through rural north Florida, cogitating all the while and indulging himself in logorrhea, or “spouting-out-the-mouth disease.” Where does this incessant garrulousness lead our hero, Hezekiah? Where is his ever-going-forward getting him? To the same place all of our ever-going-forward—really more of a circling round and round, rather than going forward—is getting the rest of us here on God’s green earth.

Published in August, 2019, U.R. Bowie’s longest book: Sama Seeker in the Time of the End Times: A Spy Novel in Two Volumes (300,000 words).

For more on “Sama Seeker,” go to Books and Products page

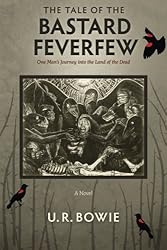

Big news at the turn of the New Year, 2018. “The Tale of the Bastard Feverfew,” by U.R. Bowie, has won the 2017 Dactyl Foundation Award for Literary Fiction and an honorarium of $1000. Many thanks to V.N. Alexander, director of The Dactyl Foundation. I am also beholden to Gen Aris, who did such a great job editing the book, and to Raghu Consbruck, graphic artist, who put those lovely redwing blackbirds on the cover.

Journey into the mind and writings of U. R. Bowie, Ph.D., accomplished author and retired professor. Bowie’s works of literary fiction reflect Russian influences and insights from 30 years as a professor of Russian language, literature and culture. His extensive resume on the ABOUT page highlights his work and trips to Russia and an exceptional career.

Books available now on Amazon:

http://www.amazon.com/U.R.-Bowie/e/B00QKSKAW4

Robert Bowie, (pen name U.R. Bowie), was raised in Central Florida and graduated from the University of Florida in 1962. He studied Russian in the U.S. Army (nine-month intensive at the Defense Language Institute) and then earned an M.A. at Tulane University and a Ph.D at Vanderbilt University. For thirty years (1970-2000) he taught Russian language, literature and culture at Miami University, in Oxford, Ohio. He has had an extensive career in Russia, spent a year teaching in Russia on a Fulbright Scholar Grant and has worked as a consultant for American business on Russian mentalities. Among his courses at Miami University was one on folklore and mythology, which included discussion of the hero’s journey and Siberian shamanism.

For an extensive look at Bowie’s accomplishments, travels in Russia, photos and variety of writings see his full resume on the ABOUT PAGE. Bowie’s latest trip to Russia was with the Patch Adams Clown tour in 2016. A fascinating diary account is on the MY BLOGS page – just scroll down.

Information and Press Releases are on the NEWS PAGE.

Lectures and Book Signings will be posted here and on the EVENTS PAGE.

Some of the reviews from Amazon are on the REVIEWS PAGE.

The INTERVIEWS page has six interviews.

Bowie’s blog is “U.R. Bowie on Russian Literature,” which features, in addition to criticism of Russian literature, translations of Russian poetry into English, nonsense poems from the pen of Bobby Goosey, and book review articles on various writers.

Books, products, and a link to Amazon are on the BOOKS/PRODUCTS PAGE.

A few book synopses below, additional ones are on Books/Products Page.

HARD MOTHER

Cover art for “Hard Mother”

HARD MOTHER (A Novel in Lectures and Dreams)

The year is 2021. The world is slowly recovering from the Great Catastrophe of 1996. You say there was no worldwide catastrophe in 1996. This is a work of fiction, and in this work there was. A middle-aged woman, Rebecca A. Breeze, professor of Russian literature at Oogleyville State College (Mass.), in the midst of a breakdown, has been forced by her superiors to consult a therapist. She refuses treatment by modern methods of drug and machine therapy, but agrees to describe her violent dreams. “The dreams…Russian literature sends them to me. Jesus Christ has a lot to do with it as well, but mainly it’s Russian literature.”

The dreams of Prof. Breeze constitute an extensive manuscript, the tale of the crazed Ultimian writer Eugene Ispovednikov (“The Shriver”) and his return to his native Ultimia—an imaginary country resembling Russia—where he foments a revolution and is crowned king in 1992. Disillusioned by the Catastrophe—a pandemic of bubonic plague that has left the whole world in chaos—he sets out on a pilgrimage eastward in 1999, seeking what he terms “The Unbearable Whiteness of Being.” The Shriver is accompanied by Maggie the Queen, Ivanushka the Dolt and his American compatriot Dezra MacKenzie, the Swedish mercenary Boe and his troops, the vile Bomelius (apothecary and physician to the king) and a convert from the Urinator faith, Foka Yankov.

A year later, at the turn of the Millennium, after numerous tribulations—encounters with violent sectarians of every stripe: including the Anti-Prepucors, who abhor foreskins, and the dread Castrates, who introduce our heroes to the “baptism in fire”—what remains of the Shriver’s party reaches the summit of the Magic Mountain of Dura, where the Whiteness is.

Rebecca Breeze narrates her part of the story from the year 2021, but none of the action takes place in that future time. The chapters set in Ultimia (1992-2000) alternate with chapters describing the adventures of an American professor in the Soviet Union of 1983. John J. Botkins, Jr., the prototype of Ivanushka the court fool in the Ultimia chapters and the central protagonist of the book, runs amuck in Communist Russia. He violates Soviet laws with impunity, steals Lev Tolstoy’s bicycle from the Tolstoy Museum in Moscow, sneaks into the Spartakiada rowing competitions disguised as an Estonian athlete, urinates against the Kremlin Wall—all the while propagating the joys of homosexuality, the efficacy of laughter, and the glory of possessing a foreskin.

The Botkins chapters complement the picaresque in the chapters set in Ultimia. Pale refractions of the modern-day characters show up in future time, and the same themes are recurrent: the myth of eternal return, the meaning of laughter, the human obsession with violence, sex and scatology, the Russian soul, fathers and sons and daughters and mothers (including the Earth Mother), the yearning to perpetuate the species—while yearning simultaneously to smash all of life to smithereens—the significance of Jesus Christ in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

As the novel progresses, the role of Rebecca Breeze becomes more and more central. She is the medium through which both the Botkins story and the Ultimian picaresque—the tale of the Shriver—pass. Towards the end of the book she abandons her therapy and makes plans to go out into the very world of violence that dominates her dreams. Like Botkins, MacKenzie and the Shriver, she is seeking her own “Unbearable Whiteness of Being,” and at the book’s conclusion she is on the verge of finding it.

Hard Mother is a highly ambitious comic novel. Like any comedy in the genre of literary fiction it is undergirded with high seriousness. A book with lots of action and even more food for thought, Hard Mother is influenced, most prominently, by the works of Gogol, Bulgakov, Marquez, Nabokov, Flannery O’Connor and Philip Roth. The reader should not approach this novel with an apple in one hand and a scotch in the other. The reader should be prepared to have his/her settled notions shaken up in interaction with this book, to fight and scratch and be offended. Any literary art is, of necessity, offensive, but is also, one hopes, efficacious and good for the soul.

GOOGLEGOGOL

GOOGLEGOGOL: Stories from the Data Base of Russian Literature, Inc.

Bowie writes in the grand tradition of Russian literature. “Googlegogol” consists of thirteen short stories, based (thematically, biographically, or stylistically) on Bulgakov, Bunin, Chekhov, Gogol, Dostoevsky, Nabokov, Tolstoy, and others. The entire production is refracted through the consciousness of that quintessential deranged master of Russian prose: Nikolai Gogol.

Some of the stories are set in Russia, others in the U.S. Some are written in purely realistic style, but the collection as a whole owes much to Russian modernism. An example of the realism is “The Death of Ivan Lvovich,” which tells the tale of the brief life of Tolstoy’s last and most beloved son, Ivan, as narrated by Ivan Bunin—winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1933. Bunin, who is eking out a poverty-stricken life in the south of France, while Hitler’s forces are invading Russia, looks back on the year 1895—when, as a young writer, he visited Lev Tolstoy in Moscow and found him grieving over his dead son. “Running Thoughts” is a stream-of-consciousness tale that takes the reader into the mind of Tolstoy, on the evening in 1910 when he made his decision to flee his Yasnaja Polyana estate and his intolerable life—and ended up running into the arms of Death.

Several stories describe events in the life of Fyodor Dostoevsky. “Man Beating Man Beating Horse” relates an episode that occurred in 1837, when Dostoevsky, his father and brother were on their way to St. Petersburg, where he would enroll in the Academy for Military Engineers. “Something in the Way of a Parricide” tries to get a handle on the story of the “murder” of Dostoevsky’s father in 1839, while “Executed (Almost)” relates how Dostoevsky was put through the ordeal of a fake execution in St. Petersburg (1849).

Other stories range far from the style of traditional Russian realism. Owing much in its themes and style to Gogol and Bulgakov, “Shoes Run Amuck” describes the misadventures of a man who—much to his subsequent chagrin—robbed the grave of Nikolai Gogol in 1931, on the day when Gogol’s body was disinterred for reburial at Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. “Hobnob” uses Nabokovian tropes to recreate a pale version of the great Nabacocoa and describe his proctoring of an exam in Ohio, 1952— and his interactions with the mind of one of the students taking that exam.

Several stories are written in a Chekhovian vein. “The Lady from Berdichev” is the tale of an old lady living out her life in Brighton Beach, while ever yearning back toward her birthplace of Berdichev, as Chekhov’s three sisters yearn for Moscow. In “Divertimento for Strings and Structure,” a story into which Raymond Carver pokes his nose briefly, Chekhov makes a personal appearance in the flesh (or at least in the mind of the hapless protagonist).

Other stories feature highly unusual characters or narrators. “Anteayer” is a modern tale of schizophrenia, a story of a young woman who leaves Russia for the American Dream, only to find that the only dreams she knows how to dream are Russian dreams. The lead story, “Recruiting,” describes obliquely how Russian Literature goes about gathering its personages and images, while its companion story, “Chimeras,”—the last in the collection—is a tale of Russian nesting dolls; open one up, and whoops, there’s a new narrator or author inside, and then open that one up and whoops, there’s still someone else. “The Riddle of the Duck” is, primarily, about Russian mentalities, the way Russians can hold simultaneous contradictory notions in their minds. It features a man who may or may not be Lee Harvey Oswald, still alive on the fiftieth anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination.

A brief word about the cover art. The front cover depicts a scene from the famous fabulist Ivan Krylov, his tale (“Quartet”) of how a nasty and uppity monkey decided to organize a string quartet. The monkey recruited an ass, a goat and a bear, and they all set about sawing away on their instruments; only to discover that none of them had ever learned to play an instrument. The back cover shows three of Russia’s finest writers—Lermontov, Pushkin, and Gogol—mulling over life in general, while cogitating over the back cover copy beneath them and the way Russian literature is presented in Googlegogol.

THE TALE OF THE BASTARD FEVERFEW

FROM THE BACK COVER:

Correctional officer J.D. Hemsler thought he had the routine down. In the morning you go into the belly of the beast; in the afternoon you come back out. Something like the way a Siberian shaman goes on a healing quest into another realm, where he is taken apart, put back together, but always returns with the magic boon. Then came the day when Hemsler was trapped in the belly of the beast. Taken apart but not put back together. The Tale of the Bastard Feverfew is the story of a prison riot in Ohio and the struggle of one hostage guard to survive. The book is structured on the pattern of the hero’s journey in folklore and mythology (Departure—Initiation—Return).

Yea, lo, behold the mystery of dismemberment, which is life in time.

The fog had lifted. In the sunny skies above the guard towers and razor wire redwing blackbirds swirled around, reveling in their own harsh calls, in the carnal reality of their existence. It was 2:20 p.m. Correctional officers Josiah D. Hemsler and Datrolt Correll were in the L-5 locked-off stairwell, the so-called “safe haven,” listening to the inmates pound on the reinforced concrete wall with universal weight bars. When he saw the concrete start to give Hemsler knew he was dead. He even said as much to his fellow officer, in a voice so calm he surprised himself. He said, “Datrolt, get ready to die.”

GOGOL’S HEAD

BACK COVER COPY: “Gogol’s Head”

In June, 1931, the body of Nikolai Gogol, great writer of the Russian land, was exhumed at the Danilov Monastery in Moscow, where Gogol’s remains had rested since his death in 1852. When the coffin was opened the head was missing. Or was it?

What about other myths? Was the body turned on its side, or upside down; were there scratch marks on the underside of the coffin lid? In his lifetime Gogol’s contemporaries sought incessantly to figure out this inscrutable man. They never could, so they made up stories about him.

Gogol’s Head examines the implications of one such story. It tells the tale of the missing head’s Gogolian fate. Mixing in details from the life of the writer to create a hybrid work—a blend of biography and fiction—the book introduces one Adrian Lee Nule: a graduate student in Russian literature and a Gogolian character in his own right.

Reseacher Nule pursues the head in its new life, as inspiration for the evil machinations of Joseph Stalin, then strives to consummate the mystical third finding of the head. Replete with Gogolian absurdity and high comedy, Gogol’s Head features the writer himself in semi-fictional scenes; it is written in a parody of Nikolai Gogol’s own style.

ГОГОЛЯ ГОЛОВА

GOGOL’S HEAD

Or

Skullduggery

Or

The Misadventures of a Purloined Skull

A Gogolian Novel

(With Gogolian Biography Appended)

U.R. Bowie

Series: The Collected Works of U.R. Bowie, Volume Eleven

Ogee Zakamora Publications, 2017

Copyright © 2017 by Robert Lee Bowie

All Rights Reserved

ISBN-13: 978-1548244149

ISBN-10: 1548244147

Front Cover Illustration:

N.A. Andreev, Medallion on Enclosure

of Nikolai Gogol’s Grave

(Danilov Monastery, Moscow, 1909)

Epigraphs:

If mere creative force is to be the standard of valuation, Gogol is the greatest of Russian writers. In this respect he need hardly fear comparison with Shakespeare, and can boldly stand by the side of Rabelais. Neither Pushkin nor Tolstoy possessed anything like that volcano of imaginative creativeness.

… D.S. Mirsky

Nobody can ever imagine what Gogol was really like. From beginning to end everything about him is incomprehensible. The individual features are blurred, inchoate—they refuse to add up to anything.

… Anna Akhmatova

What are you like? As a person you are secretive, egotistical, arrogant, and mistrustful, a man who sacrifices everything for fame. As a friend what are you like? But then, do you really have any friends?

… Pletnyov letter to Gogol, October, 1844

Дорога, дорога—дорогая дорога—дорога мне дороже всего (The road, the road—the dear road—dearest of all to me is the road).

… Gogol letter to Pogodin, October, 1840

The diver, the seeker for pearls, the man who prefers the monsters of the deep to the sunshades on the beach, will find in “The Overcoat” shadows linking our state of existence to those other states and modes that we dimly apprehend in our rare moments of irrational perception.

… Vladimir Nabokov

Вместо Предисловия

In Lieu of an Introduction

This is the story of a head, and the story of the man who lost his head, and the story of what happened to the lost head. We begin with background on the man. In the process of telling the story of the purloined head, we tell—in lieu of a biography—a truncated version of the life of the man. We cut through all the lies and establish the truth.

Adrian Lee Nule, ABD

Madison, Wisconsin,

March 20, 2015

OWN:

The sad and like-wike weepy tale of wittle Elkie Selph

Bowie’s novella OWN is a cautionary tale exhibiting strong creative writing skills with a dramatic and provocative story about a mass shooting.

FROM THE BACK COVER:

My name’s Elkin (Own)Selph, from Tocotano, GA. I love ole Georgie-what’s not to love? Not nobody caint not love the good ole sod-off Blue Ridge Mountains of NE Georgie.

Thang is, doe, I ain’t but wah-plach fifteen, and I got me like-wike real horrorshow woman problems, Now why did a ding-blinn Glock handgun get into the dits-blitz picture?

So here sets ole Own, all on his ownsome-lonesome, in a dark school cafeteria. Surrounded by scads of like-wike blinn-dead classmates. BAM BAM BAM BAM.

Quid nunc? NOW WHAT?

U. R. Bowie’s OWN is a fascinating story in the genre of literary fiction that can promote essays and discussions about contemporary and serious youth issues. Please see the OWN NOVEL page and consider the OWN Mission to help spur discussions on gun education, legislation, safety and the challenges of youth. You will also find extensive notes on the OWN MISSION and an OWN Lesson Plan for teachers.